I picked up The Trial, probably on a whim. I remember having doubts about it—sparked by a video analysis I’d seen—but just as the book itself suggests, you don’t need to rely on other people’s opinions. Every interpretation is just another opinion.

The novel is overflowing with details, dialogues, and digressions that lead nowhere—like walking through a mind consumed by anxiety and uncertainty. The legislative processes, the courtroom procedures, the side characters—they feel like dreams mimicking reality, or maybe reality mimicking dreams.

One line that stayed with me came from the priest in the cathedral:

“You accept it as necessary.”

And another:

“The court accepts you when you come, and lets you go when you want to leave.”

We never learn what crime Josef K. committed. But we live through the internalized guilt, the weight of social judgment, the unspoken shame of disappointing people—when you don’t measure up to the roles they project onto you. A classic Kafka move: strip away the event, and make you feel the punishment anyway.

Strangely, finishing this novel reminded me of medicine as a profession—especially the journey since I enrolled.

A slow-burning fear of failure.

The swelling weight of expectations.

The disillusionment with the system.

The depersonalization of people.

The quiet death of empathy.

Everyone talks about Transference and Countertransference, but no one wants to talk about the dehumanization we inflict daily—when poverty becomes a stigma, when trust in a public institution becomes a crime, and when being average is seen as moral failure.

And yet, this too is just another opinion.

In The Trial, everyone is cheated, deluded, and emotionally detached. The only ones who seem to function are those who don't care—who move through the world like ghosts, untouched by doubt.

But those who question?

They are punished.

They die like a dog.

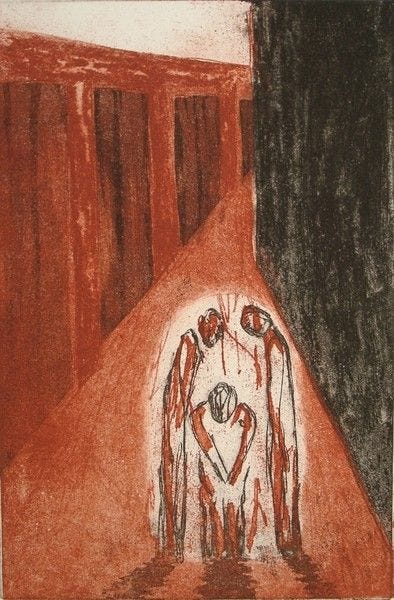

In The Trial, people don’t really see each other.

They just move past one another. Not to connect—but to complete a function.

Jobs are done without understanding. Conversations without intention.

Most people you meet feel like hollow containers—stripped of depth, following orders like machinery, with barely a shred of their humanity intact.

Even the women, like in any other Kafka story, are mysterious and transactional. They never become companions in whom the protagonist can place trust. They exist as potential solutions—a way to fix things, navigate systems, open doors.

But none of them ever get Josef K. where he wants to go.

And that part hit something in me.

In my life, women rarely go past a certain stage. Either I build a barricade. Or I quietly drive them away. They’re there when there’s a reason. And when the reason fades... it’s up to them whether they want to stay.

Though I’ll admit—part of me always wants them to hang somewhere in the middle.

Another classic Kafka move.

Sometimes I wonder if turning out like Kafka doesn’t take much—

Just daddy issues, a few bad experiences with women, and a world that makes less sense the more you try to understand it.

It sounds like an interesting novel. It's sad to think this is how the world was to Kafka.