I came across The Stranger by Albert Camus three years ago in a second-hand bookshop. The title seemed to speak directly to me, so I bought it on impulse. At that time, I was just beginning my journey as a reader, navigating through a period of upheaval and emotional dullness. Everything around me felt grey, monotonous, and distant. When I finally opened the book, I found myself absorbed. I couldn’t stop reading. Perhaps it took me three sittings to finish it, but the intensity with which it resonated with me has stayed ever since.

The Stranger begins with one of the most striking and disquieting opening lines in literature: “Mother died today. Or maybe yesterday; I can’t be sure.” From the outset, the protagonist, Meursault, reveals his indifference to societal expectations. He is detached from the conventions of grief, unable to muster the expected emotions at his mother’s funeral. Instead, he focuses on the glaring sun and his physical discomfort. This detachment sets the tone for the rest of the novel, where Meursault drifts through life, unbothered by the moral and emotional frameworks that govern others.

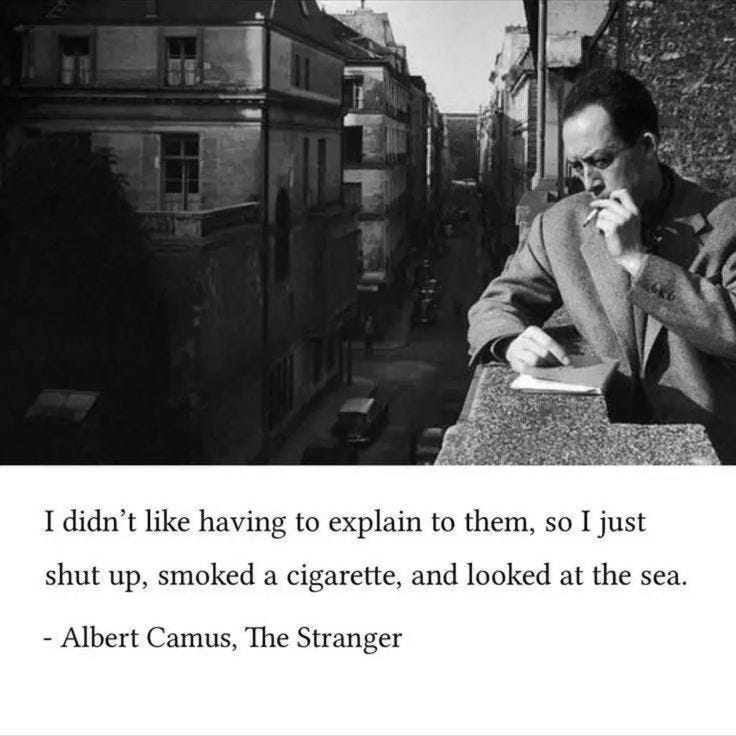

When I first read Meursault’s story, I felt an uncanny connection. His apathy mirrored my own sense of disinterest and detachment. I wandered the streets with a hand gripper in my pocket, clenching it absentmindedly, and feeling just as disconnected as Camus’ protagonist. There was a moment in the book when Meursault says, "I had only a little time left and I didn’t want to waste it on God," as he waits for his execution. This rejection of convention, his refusal to invent meaning where he doesn’t see any, struck me deeply.

But the moment that lingered most vividly in my mind came from the end of the book when Meursault recalls something his mother had once said: "No matter how hard one's life is, one can always find something to be happy about." Sitting in his cell, awaiting his death, Meursault reflects on her words as the sunlight illuminates the space: “For the first time, in that night alive with signs and stars, I opened myself to the gentle indifference of the world. Finding it so much like myself — so like a brother, really — I felt that I had been happy and that I was happy again.” It was in this acceptance of life’s absurdity that I found both solace and freedom.

To understand The Stranger, one must also understand the cultural and historical context in which Camus wrote it. Published in 1942, during World War II, the novel captures the existential crisis of a world unravelling. Camus was a pied-noir, a French Algerian, living in a society rife with colonial tensions. His experiences in Algeria’s sun-soaked yet oppressive landscape permeate the novel, shaping its setting and mood. The colonial backdrop underscores Meursault’s trial, where he is condemned not for his crime—the murder of an Arab—but for his refusal to conform to societal norms. His indifference to his mother’s death, his lack of faith, and his honesty about his emotions shock the jury more than the murder itself.

The Stranger is a cornerstone of existentialism, a philosophy concerned with the absurdity of life and the search for meaning in a meaningless world. Camus, however, rejected the label of an existentialist, aligning more with his concept of the "absurd." He believed life had no inherent meaning but that humans must live authentically, embracing life’s absurdity without resorting to false hope or despair.

The novel’s brilliance lies in its ability to challenge readers’ assumptions about morality, justice, and living authentically. Camus’ stripped-down prose mirrors Meursault’s emotional barrenness, yet it is imbued with profound philosophical insights. Reading The Stranger wasn’t just an intellectual experience—it was deeply personal. It held up a mirror to my struggles with apathy and disconnection, and in doing so, it offered me a strange sense of comfort.

Looking back, I picked up The Stranger on a whim because its title spoke to something within me. But what I found in its pages was far more than I expected: a haunting exploration of life, death, and the gentle indifference of the universe. It’s a book I’ll carry with me, not just for its philosophical depth but for the way it made me feel seen at a time when I felt invisible.