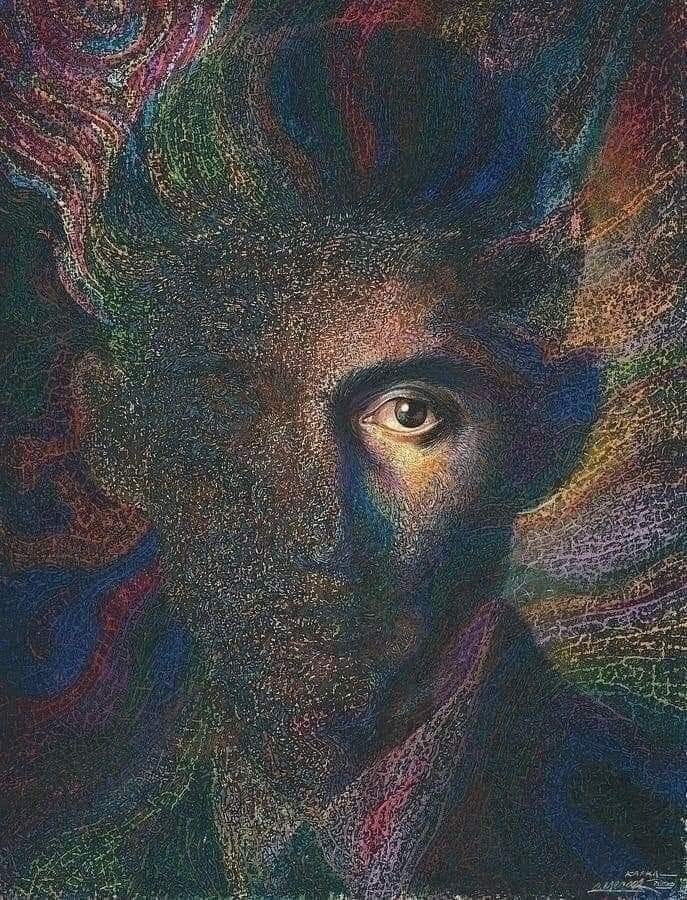

I had wanted to read Kafka's Letter to My Father for a long time. I finally read it this year—or perhaps it was last year. It took me three separate sessions to go through the entire book. After the first session, I took a screenshot of some passages and posted them on my WhatsApp status. A very close friend of mine noticed and asked about them, so I recommended the book to her. She completed it that very day and shared a little about her thoughts. It was a simple exchange, yet somehow it felt deeply precious to me.

To be honest, as I was reading the book, I saw many parallels between it and my own life at the time. It felt as though I was reading what I had long wanted to tell my own father. I think this might be true for anyone who has experienced stern and authoritarian parenting. I’ve often heard my father and aunts reminisce about the harshness they endured in their own childhoods, only to remind me how “easy” my life has been in comparison. Sometimes, the comparisons between me and my father’s physicality would come back to haunt me. I had been frail and short for much of my teenage years, and though I’ve grown taller since, I’m still comparatively weaker. Even now, I’m only an inch shy of matching his height.

But enough about me. Kafka’s letter reveals a great deal about how authoritarian parenting can leave profound imprints on a child’s psyche. The power parents hold over their children’s intellect, emotions, life decisions, and thought patterns is immense. Kafka’s words feel like the confessions of a prisoner—someone who has long wished for freedom yet has grown so accustomed to the prison’s confines that the idea of leaving becomes just as terrifying as staying. Imagine being told,

“You can leave this prison anytime, but you can never come back.” The choice itself becomes an ordeal, trapping you in an endless cycle of doubt and fear.

If there’s one thing I would say, it’s this: You should absolutely give Letter to My Father a read. Perhaps, like me, you’ll find words that resonate deeply with your own experiences. And I think that’s enough—to know that you’re not alone. It makes the world feel just a little less frightening and lonely.

Here are some quotes from the book that stood out to me:

"My writing was all about you;

all I did there, after all,

was to bemoan what I could not bemoan upon your breast."

"And I could never understand why you were insensitive to the sorrow

and shame you inflicted on me with your words and judgments – it was as if

you didn’t sense your own power."

"And I certainly made you ill with words; but I knew what I was doing,

though it hurt me, but I couldn’t control myself, I couldn’t hold back my words –

though I regretted them. But you landed blows with your words and you were clueless –

you never pitied anybody, not then, not later – and people were defenseless before you."

"And here was your mysterious innocence and invulnerability:

you abused others without regret, and you condemned abuse,

and said it was forbidden."

"You backed your derision with threats, for example, ‘I’ll rip you apart like a fish.’

And that was dreadful to me, even though I knew that nothing bad would happen

(yet as a young child I didn’t know this), but your words served as a sign of your power,

and you always seemed capable of doing something."

"And it was also dreadful when you shouted left and right at the table,

and tried to grab someone – or pretended to try – until mother

seemingly came to the rescue. And it appeared to a child that life existed

through your mercy, and continued as your unearned gift."

"And linked to this were your threats about disobedience and where it would lead.

When I began something which didn’t please you and you threatened me with failure,

my awe for your opinion was so great that failure was unavoidable –

perhaps at first, if not, then later."

"I lost the confidence to do anything. I was unsettled, doubtful. And the older I was,

the more solid was the material with which you could demonstrate

how worthless I was; and gradually, to a certain extent, you became right.

But again, I must say that I’m not as I am just because of you;

yet you increased what was there, and you increased it greatly;

because against me you were very powerful, and you used all your power."

"But please, father, understand me correctly:

these were completely insignificant details, yet they oppressed me, because you,

a great man of authority, could lay down rules for me, and ignore them."

"And through this I saw that the world was divided into three parts:

in the first lived the slave, me, under laws invented solely for my life but to which,

without understanding why, I could never fully adjust;

and in the second part lived you, infinitely far from me, busy ruling,

giving commands and being angry when they weren’t followed;

and in the third lived everybody else, happy and free from commands and obedience."

"And I was constantly in disgrace, either because I followed your commands,

and that was a disgrace, as they were valid only for me; or I was stubborn,

and that was also a disgrace, because I was being stubborn to oppose you;

or I wasn’t able to obey, because I, for example, had not your strength, your appetite,

your skill, to do whatever it was that for you seemed natural –

and of all things this disgrace was the greatest."

"But these aren’t the reflections of childhood, but the feelings.

I know it is my father's first time on this Earth, too.

And I know he had it worse when he was little.

But I was little too."